Bank of Canada sees economy shrinking in first quarter as second wave makes for choppy recovery – Interest rate held at 0.25%

[Financial Post – January 20, 2021]

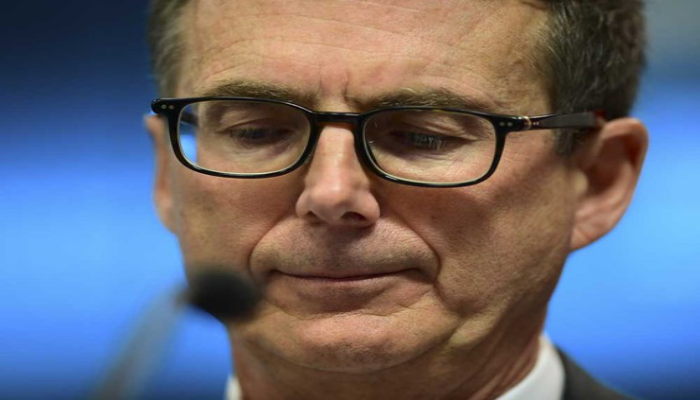

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem, an enthusiastic water skier, borrowed from one of his favourite sports to describe the current state of the Canadian economy.

“We’ve said for some time that we’re expecting a choppy recovery and, unfortunately, we’re in a very serious chop,” he said on a Jan. 20 call with reporters after the central bank released a new forecast that predicts an economic contraction this winter.

The forecast is a disappointing turn. Canada’s economy was gathering pace over the summer, but conditions turned rough ahead of the holidays as the second wave of COVID-19 infections forced governments across the country to restrict movement and commerce. Employers sent more than 60,000 people home in December, the first decline in employment since the spring, Statistics Canada reported earlier this month.

With no immediate end to the pandemic in sight, the Bank of Canada’s forecasting team concluded that gross domestic product (GDP) will contract at an annual rate of 2.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2021, after growing 4.8 per cent in the fourth quarter, thereby offsetting the boost the economy should get from the earlier-than-expected arrival of effective vaccines.

Overall, the Bank of Canada predicts growth of four per cent in 2021, compared with a previous estimate of 4.2 per cent, 4.8 per cent in 2022 and 2.5 per cent in 2023.

“We’re moving in the wrong direction right now,” Macklem said. “We’re starting off in a deeper hole. We’ve got to climb back out of that.”

The shift in circumstances highlights the fragility of the recovery from one of the most epic recessions in history. Canada’s ability to generate wealth will be determined by the public health system’s ability to keep up with the coronavirus. There’s enough money in the system to power growth, but businesses and households won’t spend it freely until the disease is brought under control.

“That is what will determine everything,” said Darcy Briggs, a Calgary-based portfolio manager at Franklin Templeton Canada.

Macklem reiterated that he intends to leave the benchmark interest rate at 0.25 per cent until some point in 2023, and that the central bank would continue to create roughly $4 billion per week to purchase Government of Canada bonds, an approach to monetary policy that puts downward pressure on borrowing costs by augmenting private-sector demand for bonds.

Extraordinary stimulus remains essential, in part, because Canada’s economy has run into additional headwinds. The immediate future of the oil industry is clouded by mediocre prices, uncertain demand and TC Energy Corp.’s decision to stop building the Keystone XL pipeline in the face of political opposition in the United States. The dollar’s appreciation has become so problematic that the Bank of Canada felt compelled to flag it as a key risk to its inflation outlook, something it hasn’t done so explicitly since 2011.

“Appreciation of the Canadian dollar creates direct downward pressure on inflation by lowering the prices of imports,” the central bank said. “Further appreciation of the Canadian dollar could slow output growth by reducing the competitiveness of Canadian exports and import-competing production. Slower output growth would also imply more disinflationary pressures.”

The Bank of Canada’s bond-buying efforts are controversial with a minority of market participants, economists and politicians who dislike the sight of the central bank using its unique power to create money so aggressively.

In theory, Macklem is testing the central bank’s ability to contain inflation, since a massive increase in the money supply should cause prices to rise. There is no evidence of that yet, as Statistics Canada on Jan. 20 reported that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased 0.7 per cent in January from a year earlier, a reading that suggests deflation is the greater threat at the moment.

“The ongoing drag from economic slack is the most important driver of inflation dynamics over the medium term,” the Bank of Canada said in its new outlook, which predicts some temporary spikes in the CPI, but concludes that inflation won’t “return sustainably” to the two-per-cent target until 2023.

Still, Macklem began the process of unwinding his bond-buying program by reminding traders and investors that the Bank of Canada doesn’t intend to be a major player in bond markets indefinitely.

The central bank used its new policy statement to tweak its language around quantitative easing (QE), as the policy is known, saying that, as “the Governing Council gains confidence in the strength of the recovery, the pace of net purchases of Government of Canada bonds will be adjusted as required.”

Policy-makers also used their quarterly economic report to point out that the central bank now holds about 36 per cent of all federal government debt, compared with 32 per cent in October, an amount that as a percentage of GDP is greater than the holdings of the central banks of Australia and Sweden, but less than the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Bank of England.

In other words, the Bank of Canada has more ammunition, but its armoury isn’t bottomless. “There’s an upper limit,” Briggs said. “We’re not there yet. We assume QE will end with the pandemic.”